Wells Fargo's Comeback

Potential for 30% Upside

Introduction

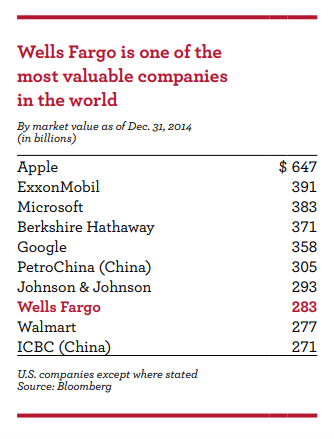

Wells Fargo needs no introduction. It’s the 3rd largest bank in America with $1.9T in assets. Ten years ago, it was the most valuable bank in the world and was held up as the gold standard for banking. Famous investors like Buffett were long time shareholders. This table from Wells Fargo’s 2014 annual report shows their place among the most valuable companies in the world.

Oh, how the mighty have fallen! Wells is the only American company on this list that has a lower market cap today than it did ten years ago. Given this horrible ten-year performance, why should you even consider looking at Wells as an investment? Well, at today’s valuation of about $220B, I think the upside / downside is quite compelling.

Thesis

At its core, banking is a very simple business. You take in deposits and you make loans. Typically, the spread between the deposits and loans is about 3%, so to grow earnings, you essentially need to grow the deposit base. From 2007 to 2017, Wells grew deposits from $300B to $1.3T and net income from $8B to $23B.

Then it all came apart. In 2016, Wells was hit with a consent order regarding sales practices misconduct. Essentially, bankers at branches were opening checking and savings accounts and issuing debit and credit cards in customers names without their consent. This tarnished the bank’s reputation making it harder to attract new business.

The next blow came in 2018 when the Federal Reserve imposed an asset cap of $1.95T on the bank. Needless to say, it’s harder to grow earnings if you can’t grow assets.

As a result of these two issues (and numerous others), Wells Fargo’s deposits and assets are almost the same today as they were in 2017. However, under the hood, there have been some meaningful changes.

Charlie Scharf, who was brought in as CEO in 2019, has been focusing the bank on areas he views to be strategic long term and cutting back on others. As part of driving operational efficiency, headcount has fallen from 263k in 2017 to 220k today. His top priority has long been a sound risk and control framework for the bank. There are signs this is working, with the sales practice consent order finally being resolved in February this year. There are also rumors that the asset cap could be lifted next year. I don’t traffic in rumors, but I believe there is upside to the stock even if the asset cap is not lifted. Here’s why.

While the deposit base is the same today as in 2017, Wells is currently paying 2.6% on those deposits vs 0.3% in 2017. With the Fed now lowering rates, a 1% drop in the deposit rate would lead to a $10B bump in net income. Obviously, this is not going to happen all at once and we’re ignoring how the rates on the asset side move, but there is clearly a potential tailwind to the net interest margin on the deposit side.

On the asset side, there are two primary components. Loans (about $900B) and securities (about $500B). The loan portfolio currently yields 6.4% vs 4.4% in 2017, so while its moved up, it hasn’t kept pace with the increased yield on deposits. The securities portfolio is worse. Yielding 3.3% today vs 2.9% in 2017. As the securities portfolio runs off (at about $25B per year for the $250B HTM book), it should continue to be reinvested at higher rates, so there’s a tailwind there. The loan portfolio yield will likely stay flat as run off is reinvested at similar rates to today. However, if the yield curve steepens, there could be a tailwind on loan yields too.

All of this makes me reasonably confident that net interest income will go from ~$47B this year to about $50B next year. This will go straight to the bottom line and assuming non-interest income stays about flat, Wells should earn about $22B in net income next year. This would be slightly less than it earned in 2017, so this is not a stretch especially given the newfound operating rigor. A 13x multiple on this seems reasonable (this is clearly subjective) and would give you a market cap of $286B. This is 30% higher than the market cap today.

The multiple is the real wild card. Pre-financial crises, Wells traded between 10-20x earnings and at ~2x book value, though they were growing 10-15% a year then. For the type of business they are today, I’d think a 13x multiple is reasonable because this implies a 8% earnings yield. The market, though, seems to believe a 10-12x multiple on normalized earnings is more appropriate. I can see the justification for this given the choppiness in earnings since 2019.

Even if none of these tailwinds materialize and non-interest income comes down 10%, the bank would still earn about 17B in NI. I’d be hard pressed to see why a multiple lower than 12x is appropriate for a bank that survived an asset cap, COVID and a dramatic 5% increase in the fed funds rate. This implies a downside of about 10%.

The other kicker for investors is that even if nothing improves operationally and they make about 20B in net income for the next five years (as they have on average for the last 12 years), they have shown they are going to return that capital to shareholders. At today’s market cap they could literally buy back half the outstanding shares in 5 years, which all else equal, means the stock doubles in that time frame. Wells has already reduced their share count by 23% in the last five years.

This spread sheet has the high level metrics that I believe are relevant to understanding Wells.

So what are the risks?

1. Investors continue to hate the banks, so it never re-rates from the current 10x earnings. This is mitigated by their ability to keep doing buy backs.

2. The focus areas into which the CEO is pushing the bank (credit cards, investment banking, wealth management etc. ) are highly competitive and it may cost Wells more to win share than they think, so non interest expenses could remain high.

3. The corporate tax rate increases. The corporate tax rate was dropped to 21% in 2017. Before that, Wells was paying about 33% in taxes. If the tax rate is raised to that level again, Wells will earn $19B in my base case above vs $22B and $15B in my bear case. This would increase the downside risk to closer to 20%.

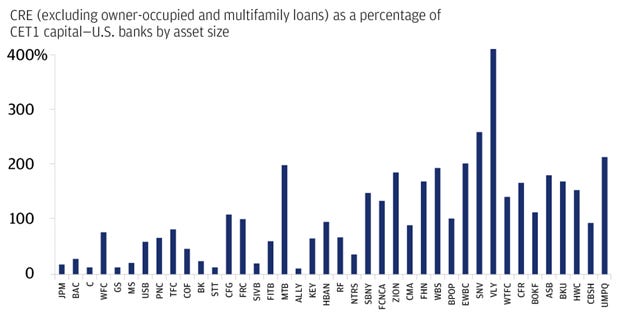

4. Credit quality deteriorates more than management is expecting. On the last earnings call, management said they believed they were appropriately reserved. Wells has a much larger percent of its balance sheet in commercial real estate (CRE) loans vs its large bank peers, so if those loans sour at a higher rate than expected it will lead to materially higher losses. This is likely the single biggest risk.

Some additional tail winds

1. The Basel 3 endgame rules are expected to not be as punitive as initially anticipated, so this could free up an additional $15B in capital that Wells could use to buy back shares.

2. The CEO in a recent interview claimed that corporate customers want to do more with Wells, so maybe they can win businesses in areas like investment banking where they’ve historically been weak (number 7 in the current league tables). This would drive non-interest income higher.

In summary, I believe that there are many things that could go well for the business here and lead to higher earnings over the next five years. At the same time, the downside is low because of a combination of a reasonable valuation and a shareholder friendly management team, so I think the risk / reward here is attractive.