J.P. Morgan May be a Buy

Price Target: $177

5/17/2021 Update - Having just analyzed Bank of America, I think I may have been a little bit optimistic in my steady state prediction for JPM shareholder returns. I am revising the number down from $28B to $27B, which lowers the price target to $177 (vs $184 previously). The remainder of the article below is unchanged.

Banks are notoriously difficult to analyze and though I’ve worked at a couple of them over my career, I can’t claim to have any unique insight into how to value them.

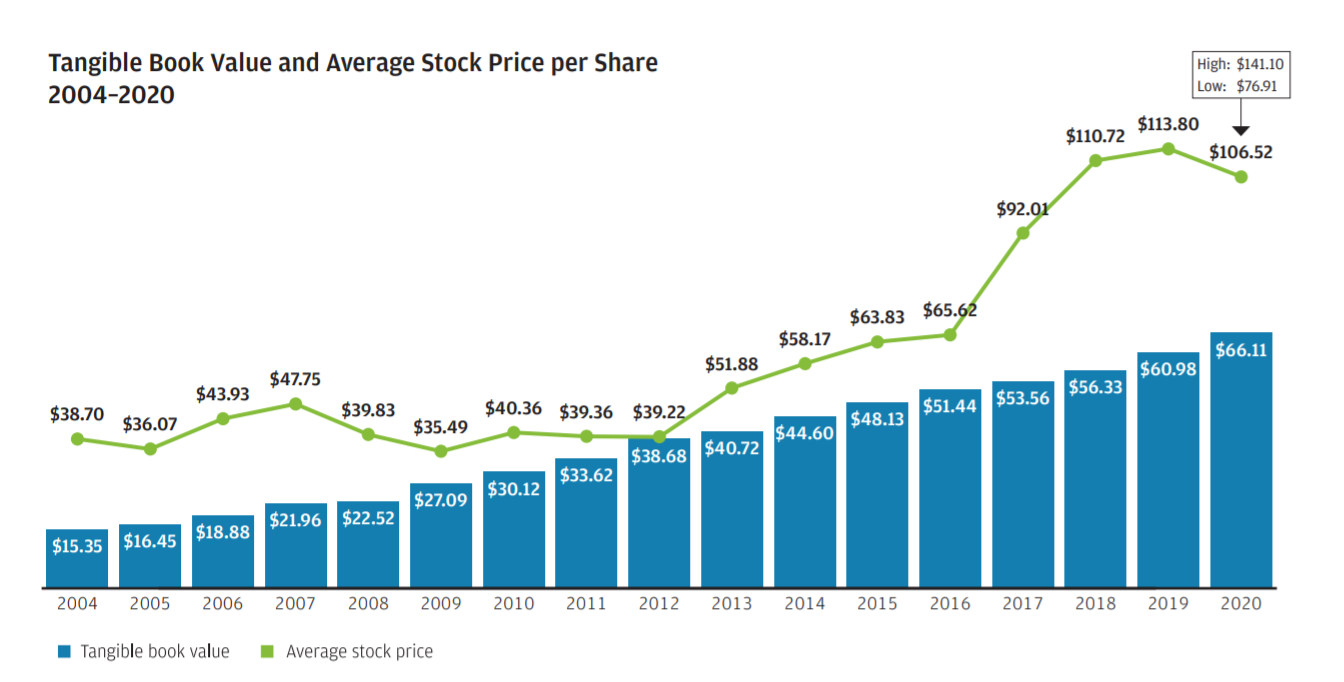

This complexity is likely part of the reason investors have defaulted to easy to calculate ratios when they attempt to value banks. Price-to-Book is a measure that’s often used to determine how ‘expensive’ or ‘cheap’ a bank stock is. While there’s certainly value to this metric (a reasonable proxy for what you’d receive as a shareholder if the bank is liquidated), I think we can do a little better by valuing banks based on the actual cash shareholders receive. This cash takes two forms – buybacks and dividends. By making a guess for what this cash return will look like going forward and by applying a multiple to it, I believe you can get a reasonable estimate for what a bank’s common equity is worth.

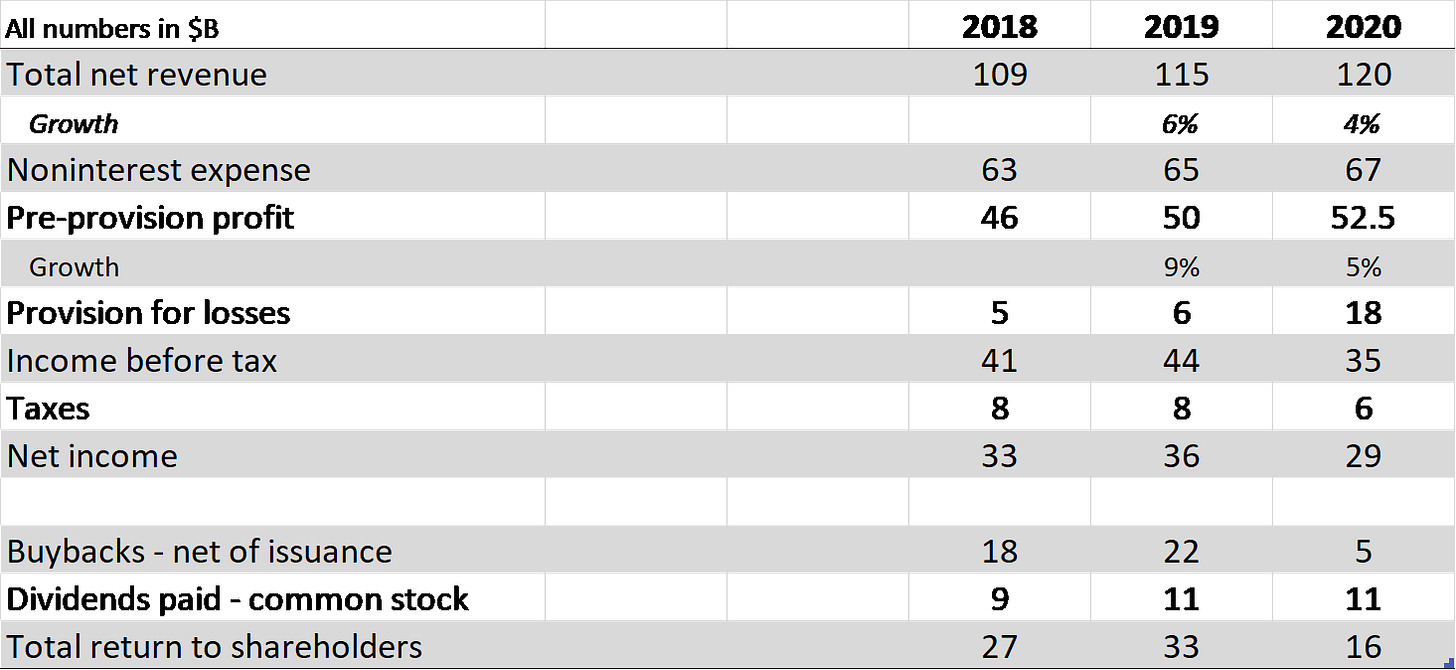

As you can see in the last line of the table below, pre-COVID, JPM returned $33B to shareholders.

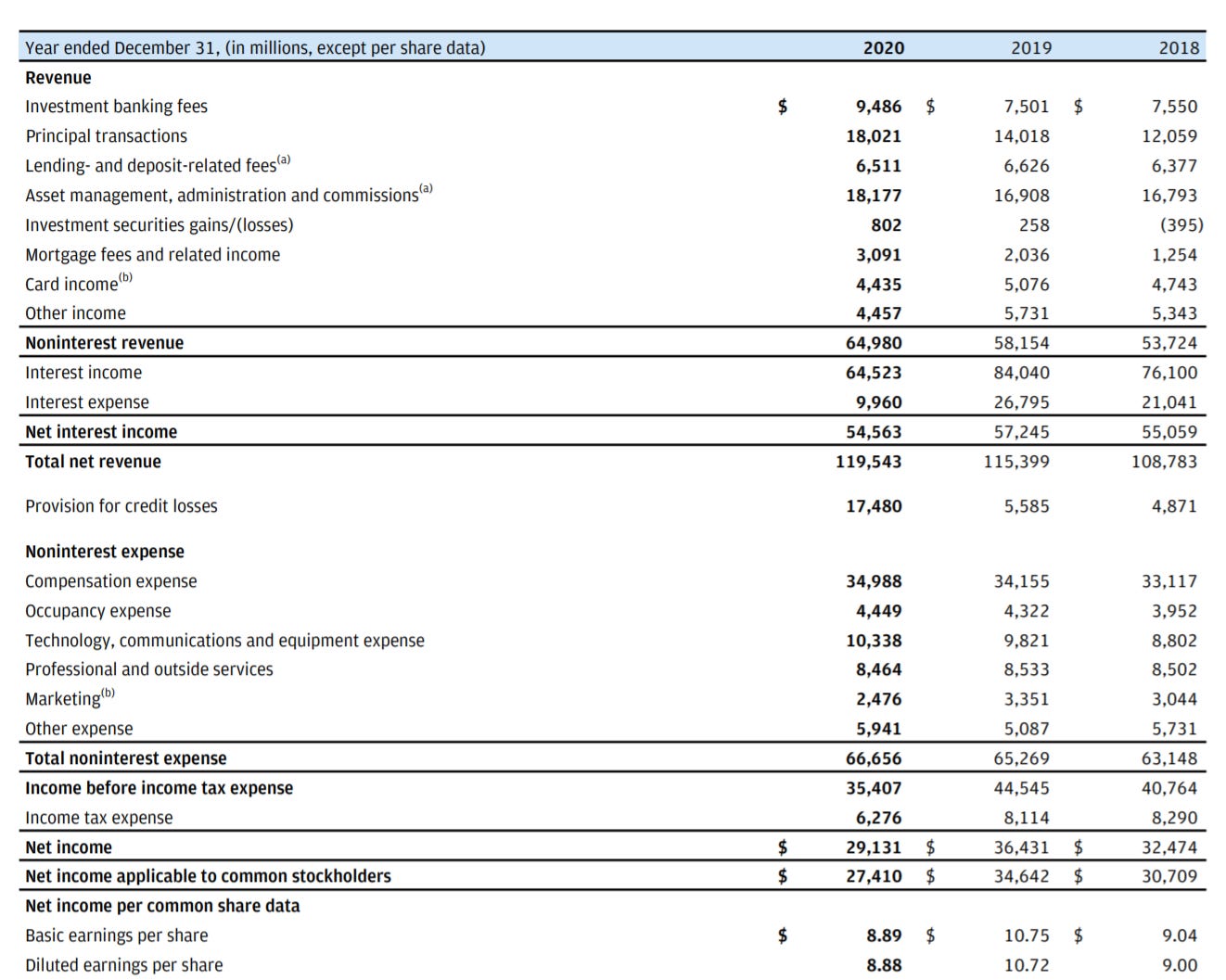

To determine whether cash generation of this magnitude can continue, I think it’s important to get a sense of JPM’s businesses and the revenues each contributes. As you can see in the table below, interest income makes up about half of revenue, with the other half coming from fees across their varies consumer and commercial businesses.

Given how much rates dropped in 2020, I was surprised to see that JP was able to take such a small hit to interest income. The steeper yield curve today should benefit interest income going forward. Historically rates on deposits have gone up much more slowly than rates on long term debt, which enables the banks to make a higher spread in a rising rate environment than in a more stable one.

2020 was a blockbuster year for investment banking, and I’m sure fees will drop to more ‘normal’ levels going forward. Asset management should be a fairly steady business going forward, while consumer debt (cards and mortgages) will be cyclical. JPM serves more than 63mm households in the US, so while there will be ups and downs, I don’t see their consumer businesses shrinking dramatically in the next decade.

I’m going to anchor long term shareholder cash returns off 2018 numbers since this was neither a boom nor bust year for JPM. My sense is that they’ll be able to return at least $28B a year to shareholders (growing at inflation) over the next 10 years. They returned $27B in 2018 and the company had a meaningfully smaller deposit base then.

Applying a 20x multiple to this ‘shareholder cash’ number, I arrive at a market cap of $560B for the firm. This represents a 22% premium to the current share price.

The reason I feel comfortable with a 20x multiple is because I don’t think the big money center banks are going to be ‘disrupted’ any time soon. The massive deposit base is going to be sticky for a long time to come. I opened a checking account at Bank of America when I first came to this country in 2007 because it was the only bank I could walk to. While I’ve since opened accounts at other banks, I still have the account with BofA and I’ll probably never close it. People over 50, who have the bulk of the liquid assets in this country, are even less likely to move their money from a bank like JPM to a fin tech startup. The same is true for corporations. If you’ve got millions or billions of dollars on deposit at a large bank and you’ve had the relationship for years, something would need to change quite dramatically for you to move your money.

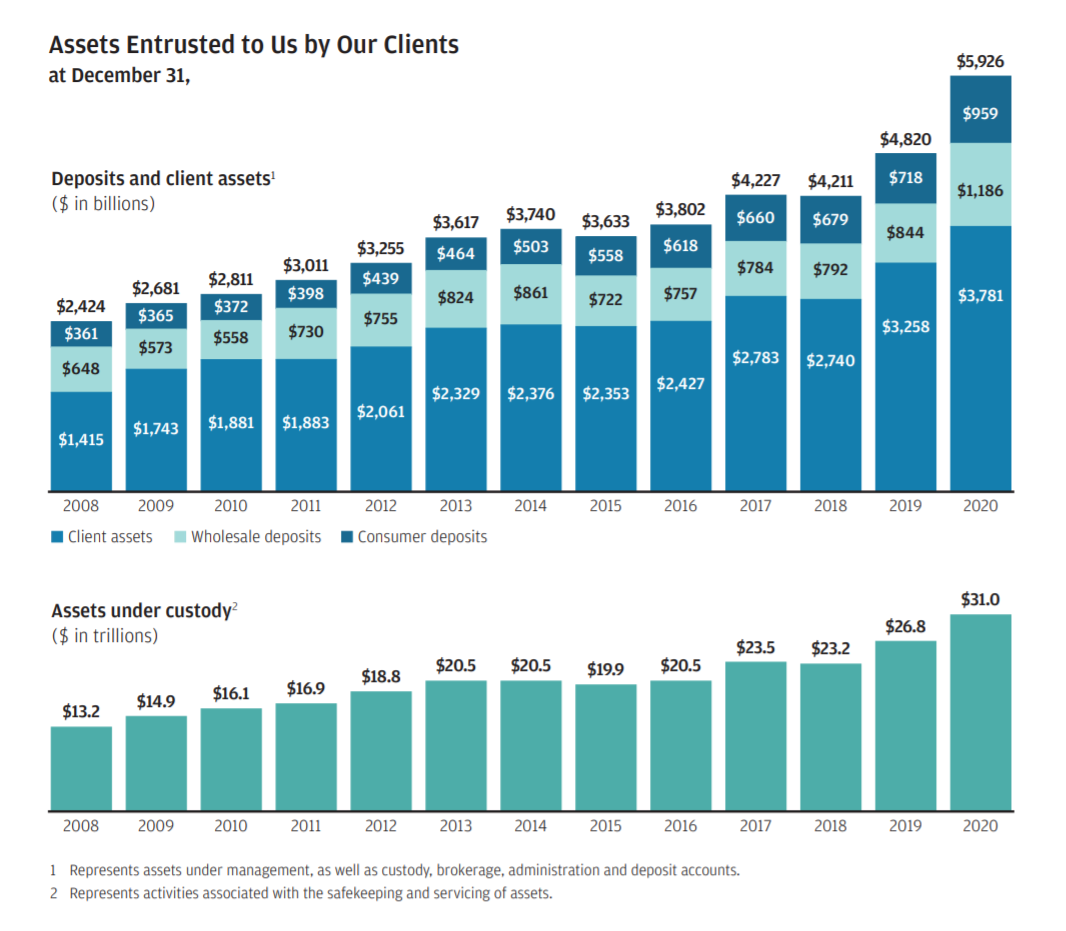

JP Morgan had $6T in client deposits in 2020 (see chart below) - that’s a massive number! It will likely shrink as companies and people start spending again, but it’s unlikely to dip below 2018 levels.

Because of these sticky deposits (even in a world where depositors earn nothing on them), I’m comfortable believing JPM will be around in 20 years in a largely similar form and likely more profitable than ever.

With this analysis, I haven’t built a full-fledged model, but you can put in your own assumptions for steady state ‘equity cash flows’ and an appropriate multiple here.

Risks

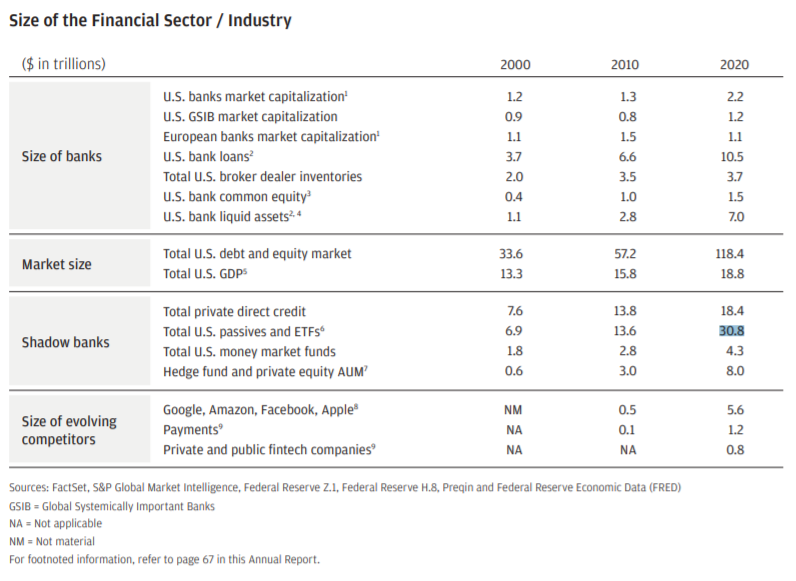

Growth of Shadow and Fintech Banking

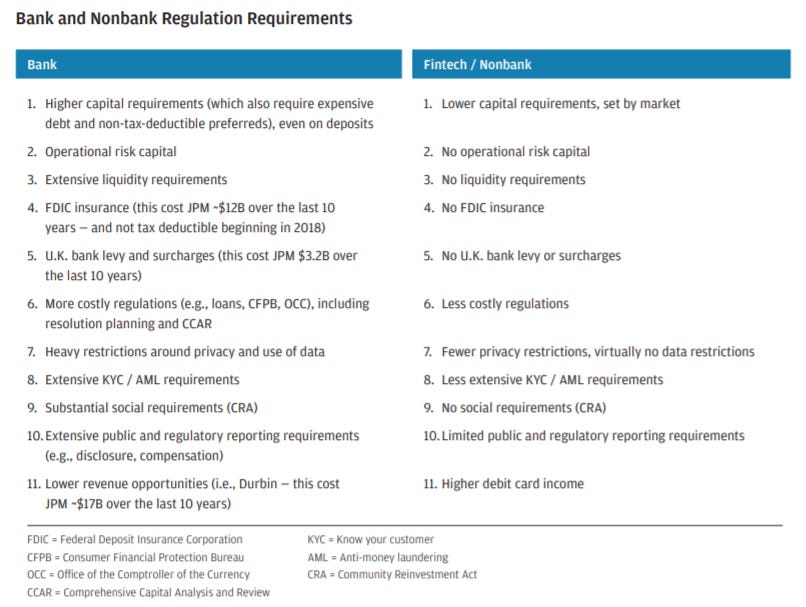

Jamie Dimon makes the point in his shareholder letter that the regulatory environment for non-banks is very different than that for the large banks. This means these entities, can potentially underprice the banks and steal market share. The chart below shows the growth of ‘shadow banks’ relative to banks and the overall economy.

He therefore calls for a level regulatory playing field. While I think this a valid concern, I think the risk is mitigated by the fact that JPM has access to cheap funding (from deposits) and should therefore be able to compete with these new entrants. Over time, if these entrants become large, I expect they will also be regulated. Below is a list of some of the current differences in regulations between banks and the fintech / nonbank companies.

Will the Market Agree?

While I may think JPM is worth at least 22% more than today’s price, the fact that banks are typically valued on multiples of book value, may mean this valuation will not be realized for a long time. If you look at the chart below, you can see that the premium to book value is the highest it’s been in over 10 years. There’s a good chance, it doesn’t go any higher.

My sense is that many investors are still wary of financials after the crises in 2009, so it’s possible these stocks will continue to trade cheaply. However, at some point sentiment may change as investors realize that the large banks are money printing machines that are largely impervious to disruption.

Jamie Dimon notes another issue for bank shareholders in his 2020 letter –

Proper capital management means consistent dividends, the ability to reinvest in your business and incentives to buy back stock when it’s cheap – not when it’s expensive. The procyclicality of both accounting and bank regulatory management virtually assures the opposite. It is one of the reasons that bank stocks may not trade particularly well.

Notes

Longevity

If you believe the author of Lifespan, which is a fascinating book, aging is a disease that will soon be treatable and people are going to live longer, healthier lives. This means that the over fifty crowd with most of the country’s wealth is going to have deposits with the money center banks for decades to come. Presumably, JPM’s highly paid staff will find a way to generate 3-4% on this cash.

An Economic Boom

Below is some food for thought from Jamie Dimon’s most recent shareholder letter. I found his take on the economy to be very insightful and is making me reassess my past bearishness for the market as a whole. I’ll have a post to revisit fair value on the S&P 500 in the next month.

Circumstances and starting points matter. Before the Great Recession, you had an overleveraged financial system and overleveraged consumers. For years after the Great Recession, there was a massive deleveraging in the United States by consumers, many investors and financial institutions, somewhat due to regulations. Today, this is not the case. In the United States, the average consumer balance sheet is in excellent shape. The consumer’s leverage is lower than it has been in 40 years. In fact, prior to the last $1.9 trillion stimulus package, we estimate that consumers had excess savings of approximately $2 trillion. Corporations also have an extraordinary amount of cash on their balance sheet, estimated to be approximately $3 trillion. And the financial system and investors have already adopted more conservative leverage requirements due to regulations – so they have very little need to deleverage. The QE in this go-around will have created more than $3 trillion in deposits at U.S. banks, and, unlike the QE after the Great Recession, a portion of this can be lent out. I have little doubt that with excess savings, new stimulus savings, huge deficit spending, more QE, a new potential infrastructure bill, a successful vaccine and euphoria around the end of the pandemic, the U.S. economy will likely boom. This boom could easily run into 2023 because all the spending could extend well into 2023.

Rising Bond Yields

Dimon again -

In 2020, the Federal Reserve bought essentially 100% of all new issuance of Treasury notes and bonds. In 2021, with the Fed’s current QE commitments, the market (not the Fed) will have to absorb $2.2 trillion in government debt – approximately 85% of which will be in longer duration maturities. This is a large number, even for the United States. We should also remember that many, if not most, buyers of U.S. debt are essentially required to buy; i.e., foreign central banks, banks, insurance companies, foreign exchange reserve managers and duration hedgers. A notable exception is investors who buy the 10-year bond to take risk-off positions. However, all of these buyers will seek out alternatives – and there are always some – if they become worried about the long-term, sustainable value of Treasury bonds. And remember, annual inflation is already running at 1.7%.